Exploring the ancient landscape of the Outer Hebrides, MEETING POINT – Within the Lewisian (Sgeir a’ Chòmhdhalaich: san gneiss Leòdhasach) at Taigh Chearsabhagh Art Gallery & Museum on North Uist is a meeting of sculpture and the art of the book. Two dimensions meet three and four dimensions in an exhibition inspired by ideas of Deep Time.

A point becomes a line becomes a fold becomes a photographic image on a page to transform into ancient metamorphic rocks suspended in the air. The fragility and transience of books, scrolls and pleated fans of paper meet the heavy glacial momentum of stone. The meaning of moments, fleeting and ephemeral – a white-frothed wave in the sea, a rope of seaweed in the sand, a striated pebble on a beach – are witnessed within the context of an island, itself a by-product of deeper forces, of shifting tectonic plates.

Sculptor Jake Harvey and visual artist and book-maker Helen Douglas make reference to the Scottish natural philosopher and father of modern geology James Hutton, whose studies of the stone of Scotland’s west coast led him to see that the world was far older than had been thought hitherto, influencing the later work of Charles Lyell and Charles Darwin.

The Outer Hebrides has some of the oldest rock in the British Isles. Principally Lewissian gneiss, it is composed of feldspar, quartz, mica, garnet and other rare, and not so rare, earth minerals. Harvey hones the pitted surface of the stone using hand-tools, in a slow, patient, meditative process. The effect is a bit like putting a pebble in water to make the colours come alive, in a satisfying sort of magic, giving him time to see universes within.

Harvey’s sculpture Infinity is quietly positioned on a window ledge in Gallery One, with views over the yard towards the bay at Lochmaddy. The sense of Uist’s landscape is ever-present. For non-locals, simply getting to the Gallery is a long pilgrimage. Austere and beautiful, it is rare to be on the island without sight of the wild North Atlantic. Sometimes a bright sheen, a mirage in the distance, more often a bracing, immediate presence. One way or another, the island and water are in constant dialogue. Climate change and rising sea-levels mean Taigh Chearsabhagh itself suffers flooding.

Infinity is shaped a bit like an egg. Formed from a boulder of Lewisian gneiss, one half is pitted, rough, matt, pale grey; the other half is honed to a smooth surface which deepens and darkens the grey revealing seductive crystals of pink garnet.

The more you look, the more the crystals seem to float like so many individually-shaped planets within their tenebrous metamorphic ocean, some close, some far away. The inner horizon of the stone (the apparent line where heaven meets earth, light meets the edge of a cosmic black hole) is speckled, soft and hazy. Roughness and smoothness merge in a spangling scatter, dense and solid yet porous with everything on the surface, yet there’s a sense of depth.

It makes me think of recent images beamed from outer space showing the infancy of the universe: a dance of hydrogen and helium. Physicists can read these images, like deducing sea-tides from the moon, interpreting deep troughs and crests millions of light years across, containing matter, dark matter and the dark energy of empty space.

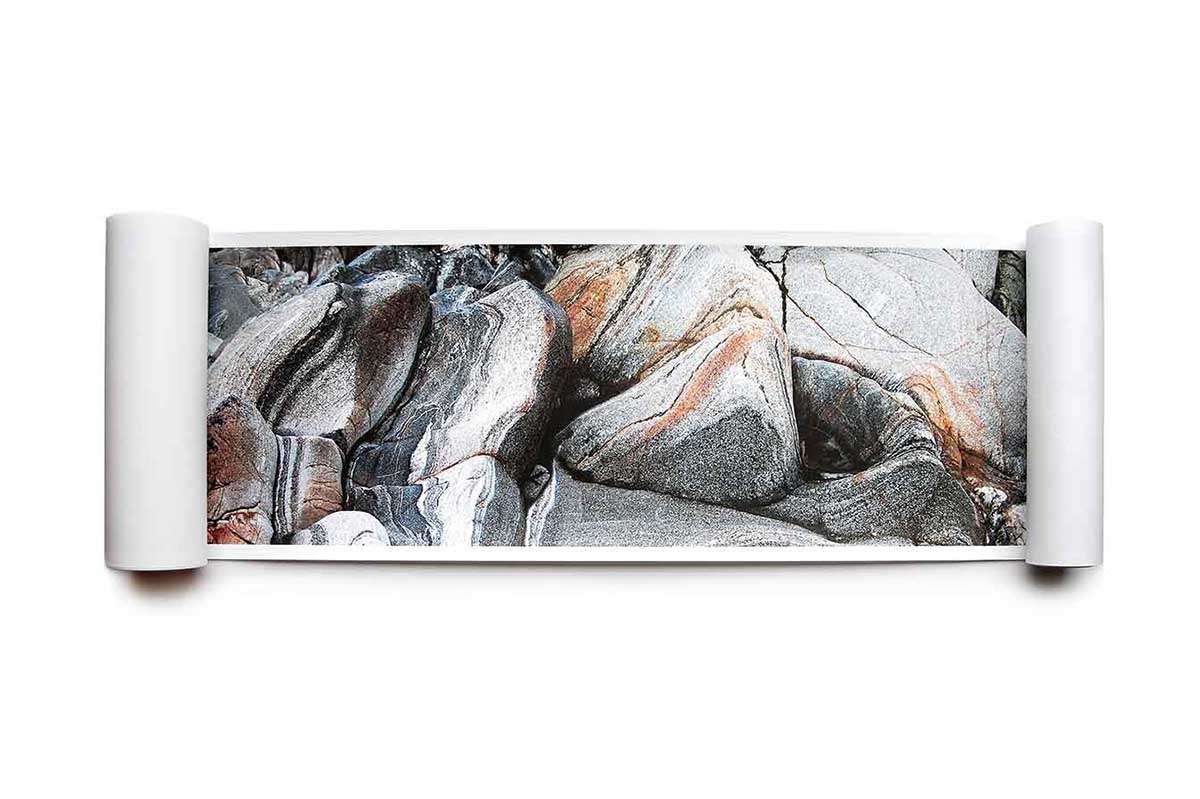

Downstairs in Gallery Two is Helen Douglas’ monumental Lewisian I. Folds and crevices of dark and light matter mingle in shades of salmon-pink and grey, charcoal and peaty brown, dancing, pulling, pushing, layered like bodies creased and curled around one another, exposing a shoulder, an arm, a thigh, concealing moonless intimacies.

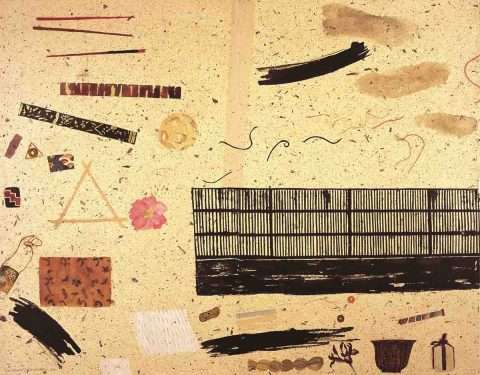

Douglas sees the landscape and time as movement, a dance, wild as a reel at a North Uist ceilidh. Wave & Rock and Rock & Wave: two concertinaed books – time folded in on itself – face one another. Non-symmetrical, deep-blue frothy-white North Atlantic breakers smacking into the rocky ochre-umber-charcoal coast; the rock with watching birds giving way again to the Sea.

The through-line of Douglas’ works is innately horizontal. Whether read from right to left or vice-versa, the scrolls and books, the concertinas and even the pleated fans are records of the passage of time. Harvey continues this through-line of time in wall-based works made from recycled cobble setts, such as Calligraphic Flow and Basalt Flow II and in vertical series such as Cladach: curve of a headland, a promontory, a pilgrimage, a vista, a splash of colour.

Harvey’s No vestige of a beginning/No prospect of an end is a quotation from Hutton’s seminal work Theory of the Earth (1788). Fifteen gneiss boulders, striated, speckled, banded, honed and rough, positioned on top of flat square slabs of dark-grey Caithness slate are arranged in a regularly-spaced grid on the Gallery floor, filling the space, suggesting the space beyond, the island itself.

Boundary, a rough-smooth dark-grey boulder of metadolerite, is raised up on a square plinth of corten steel, alluding to the molten iron thought to be churning at the centre of the Earth.

In Douglas’ Lewisian III, dark grey stone is transformed on a paper scroll into shining silver, the wet back of a slinky seal or jellyfish. Curls of seaweed recline and tiny pebbles hide as the tide surges in and out, reminiscent of waterfalls on the neighbouring Isle of Skye, catching the sun turning the mountainsides into sheer light falling.

Douglas’ book Verdant is a tangle of bright green, a smudge of blue, hazy as a distant memory of the white gold sands of West Beach on the adjacent Isle of Berneray. STONE, a set of five small hand-stitched books, contains on every page an image of a single pebble casting a short grey shadow in a white space. The sense of scale is deceptive. The pebbles could be planets; they could be speckled eggs.

Douglas and Harvey’s dance in Meeting Point describes time as a continuous flow, as something indivisible from consciousness, a constant creative current running through the rocks, the sea, the birds, the air, running through us all.

With thanks to Kate Robinson for this review.

The exhibition is set to tour to An Lanntair in Stornoway and thence to the RSA in Edinburgh, with other venues to be scheduled. Also showing at the centre until 15th August is the Uist Arts Association‘s annual exhibition, which presents a showcase of work by its members in a diverse range of media, with many of the works available to purchase – Editor