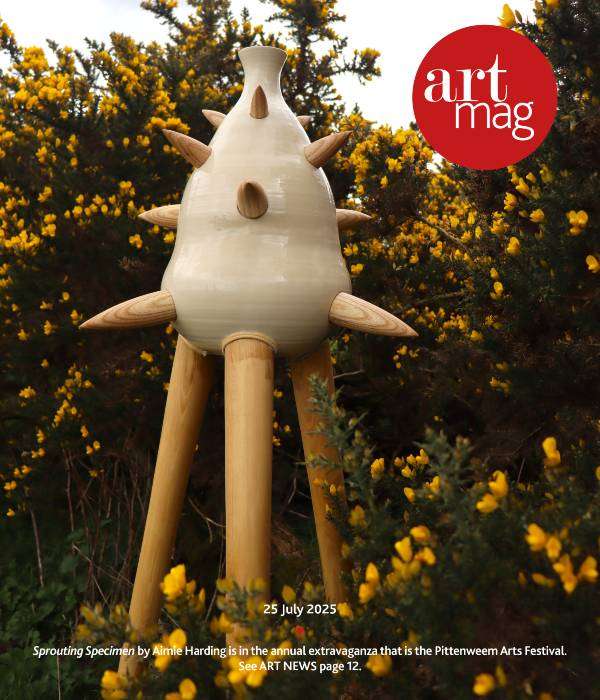

‘As a tapestry studio founded in 1912, it is exciting for Dovecot to show these important paintings… to recast Scotland’s pivotal role in the history of early 20th century art.’ – Celia Joicey, Director of Dovecot Studios.

The Scottish Colourists – Samuel John Peploe, John Duncan Fergusson, George Leslie Hunter and Francis Campbell Boileau Cadell – are now recognised as one of the most talented and distinctive groups of 20th-century artists. Their first exhibitions – in Paris in 1924 and London in 1925 – were a significant breakthrough, leading to more shows and the purchase of a Peploe still life by the Tate.

This fascinating centenary show at Dovecot Studios, in partnership with the Fleming Collection, presents the Colourists’ pioneering style in the context of their contemporaries, the influence of Post-Impressionism, fusing the Glasgow School with Parisian avant-garde and fresh vibrancy of Fauvist colours.

‘The searing impact of the Fauves turned Peploe and Fergusson from progressive tonal painters into unabashed Colourists. All four Scots were united by a fierce curiosity to be part of the zeitgeist, the spirit of the age.’ – James Knox, Director, The Fleming Collection, The Scottish Colourists (book – see bottom).

Peploe and Fergusson regularly visited France and lived there for a while, sharing an enthusiasm for French masters, Manet and Monet, and embracing a modern, radical approach to art ‘through brilliance of talent in their quest to create a new language of colour’. In 1905, Peploe moved into a new Edinburgh studio with grey walls with a hint of pink. The impressionistic study of the model Peggy Macrae, Lady in a White Dress (1907) focuses on her silvery dress against the grey-mauve decor with a flowing wash of colour, her face glowing in a soft light; a homage to Whistler’s Symphony of White portraits shown at the RSA Edinburgh in 1902.

Cadell was renowned for his portraits of elegant women, who posed in his grand Edinburgh townhouse. The Feathered Hat (1915) illustrates the influence of Manet and Whistler as he plays with technical freedom, contrasting effects of black and white, reflections in the mirror, and a subtle sense of movement.

Peploe began to paint still lifes experimenting with light and dark tones, inspired by Manet, whose work he had viewed in Paris. With a blurred sketchy background, in Flowers in a Silver Jug (1904) the eye is drawn to the white petals, glistening vase and shadow on the wall.

In similar fashion, Fergusson’s finely-textured still-life, Jonquils and Silver (1905) illustrated his aim to express ‘truth, reality through light. Form and colour, the only means of representing life, exist only on account of light.’ The silky sheen of oil paint of the gleaming silverware is exquisite.

Leslie Hunter also created his own mannered approach to still-life, echoing the influence of the Dutch old masters as shown in Still Life with White Jug (1912). Study the detail of patterned plates, apples, grapes, half peeled orange and folds of the linen tablecloth, and it will be clearly reminiscent of Le Panier des Pommes (1893) by Paul Cézanne. Hunter’s neo-classical style caught the attention of Glasgow dealer Alexander Reid who staged a successful exhibition in 1913.

Henri Matisse’s painting Blue Nude (Souvenir de Biskra) caused an uproar when exhibited in 1907 in Paris. Disregarding the natural, soft curves of the female figure, the woman’s contorted, muscular body with blue and green skin was a way to express sensuality – a trademark of his Fauvist work.

Fergusson was in Paris at the time and likely to have seen this painting; Matisse and the Fauve movement were strongly influential, and as part of a series he depicted Blue Nude (1909-10). He was now experimenting with his own vivid, vivacious style – one might say Picasso-esque: ‘Modernism penetrates beneath the outward surface… and disengages the rhythms that lie at the heart of things.’

Founded by Fergusson, The Rhythm Group were followers of the Fauves’ bright, energetic style. In October 1912 their exhibition was held at the Stafford Gallery, London, in which Peploe and Fergusson were viewed as leaders of the European avant-garde.

Matisse and André Derain spent the summer of 1905 painting in the small Mediterranean port of Collioure, inspired by the brilliant southern light, as Matisse enthused, ‘Colours became sticks of dynamite. They were primed to discharge light.’ Even in a black and white ink drawing, Port de Collioure expresses his sense of enthusiasm, quickly capturing the castle, fishing boats and trees as an intuitive visual response to the surroundings.

The Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition was also staged in 1912, and Walter Sickert criticised Roger Fry for excluding the ‘Scottish Fauves,’ praising the distinctive beauty of each artist’s work. Fry had selected revolutionary work by Picasso, Matisse, and the Bloomsbury Group. Although well aware of the cutting-edge Scots and their circle living in Paris, they were not included.

The Rhythm Group published a magazine, edited by John Middleton Murray and Fergusson, with contributions from the writer Katherine Mansfield and the artist Augustus John, who had been invited to exhibit in the Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition, but declined due to Fry’s selection process.

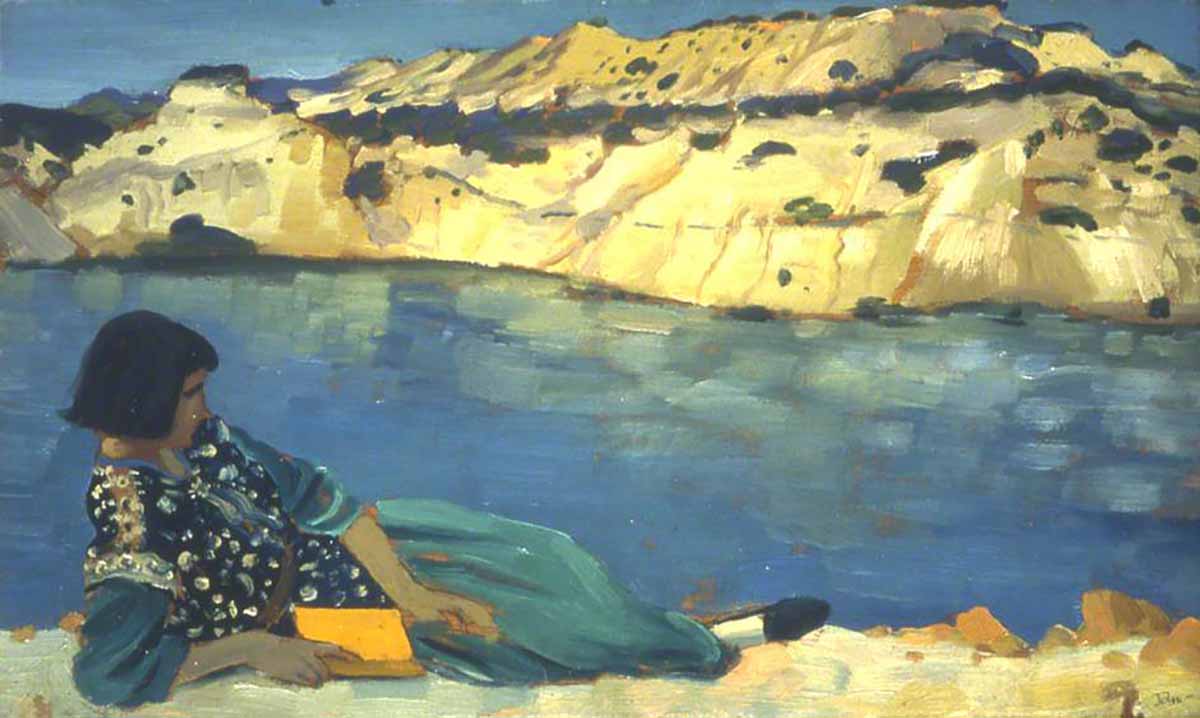

At this time, John began to create highly-coloured, expressive sketches, illustrated here in The Blue Pool (1911), which portrays Dorelia (Dorothy) McNeill, his lifelong companion and muse, beside a lake in Dorset. With a bold blue palette – teal dress, azure water – the tranquil scene shimmers in the sunshine reflected off the sandy rock.

The Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition highlighted Pablo Picasso’s dynamic Cubist portraits, prompting Roger Fry to speculate on the emergence of pure abstraction in art – ‘visual music’; many Fauve artists experimented with Cubism.

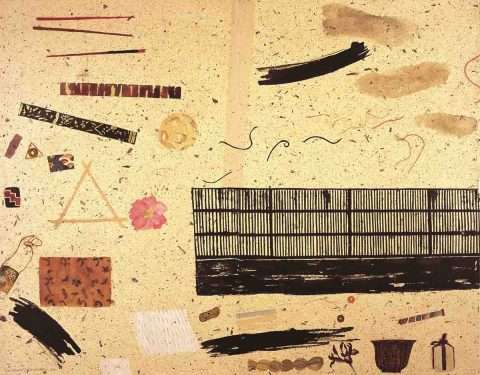

Duncan Grant was a central figure in the Bloomsbury circle of artists and writers, including Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and her sister Virginia Woolf. In 1913 Fry founded the Omega Workshops, producing furniture, pottery and textiles with decorative designs by Grant and Bell.

Flowers in a Glass Vase (1917) by Duncan Grant is a geometric, semi-abstract composition, with exaggerated flatness of form, simplicity of petals and leaves in a stylised art-deco pattern.

Vanessa Bell, renowned for her minimalist portraits and impressionistic landscapes, was described in 1925 as ‘the most important woman painter in Europe’. Like the Scottish Colourists, she travelled to the South of France to absorb the light and colour, and from January to May 1927 she rented a villa in Cassis – a fishing port on the Mediterranean coast, where she painted Baie de La Reine. Crisply-defined, curving contours of beach and hill, a slick smudge of waves, all in delicate shades of sand, ochre, terracotta to express the heat of bright sun.

Cadell first visited Iona in 1913 leading to a life-long passion for the island. Ben More in Mull (1930) is a magical view from the cottage where Cadell and his partner Charles Oliver stayed each summer. The calm sea, yacht sailing in the breeze, lapping waves on the white sand is beautifully atmospheric.

In 1913, Fergusson met the influential choreographer Margaret Morris in Paris, when she took her modern dance troupe on tour – the start of a strong creative and personal partnership, teaching dance and art classes at summer schools in fashionable French resorts. Four women in chic summer hats enjoy the sunshine on La Terrace, Dinard 1931 in a bold splash of colour and rhythmic-Cubist form, celebrating his love of France.

As well as developing the Margaret Morris Movement of dance education, she was also an unsung Scottish Colourist in her own right. Portrait of Flossie Jolley (1920) was one of Morris’ ‘Dancing Children’ – her first touring company, whose performance in a duet was praised as ‘gentle zephyrs blowing across the stage in veils of blue and grey.’ Here, Flossie expresses youthful beauty with Celtic red hair and piercing turquoise eyes, enhanced by her dress and headband.

This review just covers a small selection of the diverse range of artwork on show at Dovecot Studios. Interpretation panels take you on an insightful journey through the early 20th century to relate the story of influential friendships, inspirational travels and the innovative curators of ground-breaking exhibitions.

‘This momentous exhibition, for the very first time, shines the spotlight on the radical Scots and their contemporaries, allowing us to truly assess their achievements and place in the history of early European modernism’. – James Knox, Director, The Fleming Collection

Admission: £12 (concessions available); children under 12: free. See Dovecot’s website for more info, tours and events.

Books: The Scottish Colourists, James Knox (Fleming Collection); The Scottish Colourists, Guy Peploe (Scottish Gallery Press) – to be published 3rd April 2025.

With thanks to Vivien Devlin for this review.

David White, Online Editor, adds: bucking the news that UK galleries are suffering from a decline in visitor numbers, Dovecot Studios has announced record visitor numbers this year – 90,000 in the past 12 months, representing an increase on its annual pre-pandemic footfall by over 50%.